Deliberately Downwardly Mobile and Not Doing

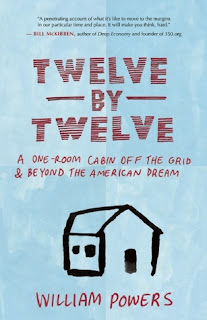

I wrote this post last year and left it to sit as a draft since then. I intended originally to continue my thoughts by connecting to two other books I was reading at the time. But those connections elude me now. Still, I want to post this so I don't lose the thoughts I had and so I remember to come back to them. Also, I want to recommend this book:

Sometime in the last two years I read a really well-written and interesting book (Twelve by Twelve: A One Room Cabin Off the Grid and Beyond the American Dream by William Powers) about the experiences of a man who moves into a tiny off-grid house in a rural North Carolina community. Powers, who had years of experience working in Latin America and Africa doing conservation and aid work, had recently returned to the U.S. and despite the relative success of his efforts at the local level, was increasingly disillusioned with what he calls a "destructive global system"(xiii). He found himself wrestling with this question: "How could humanity transition to gentler, more responsible ways of living by replacing attachment to things with deeper relationships to people, nature, and self?"

Philosopher that I am, I'm annoyed by this question, since in truth it's not really a question, it's a assertion masquerading as a question. In other words, it's a pseudo-question. As an assertion, it reads: Humanity ought to transition to gentler, more responsible ways of living by replacing attachment to things with deeper relationships to people, nature, and self.

Setting aside my annoyance, I agree with that assertion, and Powers' book is an intriguing description of the transformation that takes place in him, of the deeper relationships with people, nature, and self that he develops, during his stay in the tiny house and its surrounding communities.

I'm bringing up the book now because I've been thinking back to a scene in it where he describes an interaction he has with a father (Paul Sr.) and adult son (Paul Jr.) who have recently transitioned from professions in suburbia to life off grid on thirty five acres of woods, where they were in the process of building several tiny houses for themselves.

After a walk with the pair, Powers reflects on the deeply engrained and widely shared belief in the value of growth and development, at least amongst many residents of the United States:

To return to the passage: it has stuck with me since I read the book and I found myself many times over the past year recognizing in my own thinking and behavior an impulse "to do things, build things," to domesticate, and have "a hundred things on my list." I don't think there's necessarily wrong with this impulse to do things, but sometimes it is compulsive and non-reflective. And sometimes the things we feel compelled to do might be better left undone. I also find it intriguing to think about this urge to do things, to create something new, as a kind of "internal colonization."

I'm often caught up in this urge to do things. I find it hard to sit still or to stay focused on thinking or writing about a particular thing for very long. There's always some other thing that seems to be calling for my attention.

I'm not entirely happy with this compulsive behavior. While it can be positive insofar as it leads to learning and understanding new things, it means that it's difficult to focus on one thing long enough to go into depth and to explore its nuances.

But apart from this compulsion when it comes to ideas, I also experience it as it relates to my physical environment. Wherever I am, I feel a relentless push to create some kind of order: to pick up garbage or dead branches lying on the ground, to plant things, to build stone walls, and to make whatever processes already happening in a place more organized, deliberate, and efficient. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but when I can't create order in my environment or can't do it quickly enough, I am distressed. And once I have created order, I want to move to a new environment so that I can begin the process anew. I don't believe I behave this way out of "affluenza" or because "the richer [I] get, the poorer [I] feel;" I also don't think that it's activity intended "to fill the void," as Powers suggests.

To me, it seems more like a personality trait of mine (admittedly one that my socialization encouraged and one that has been encouraged in many of my peers as well), one connected to my urge to come to know, to develop understanding by organizing ideas in a coherent way. But I see now upon reflection that this trait is not simply about coming to understand the material world; if it was, I'd just look carefully at things, perhaps manipulate them to better understand them, and then put them back as they were. I don't do this; I change things, I am compelled to improve them.

But now I wonder, is it really improvement? Am I really making things better than they were?

Sometime in the last two years I read a really well-written and interesting book (Twelve by Twelve: A One Room Cabin Off the Grid and Beyond the American Dream by William Powers) about the experiences of a man who moves into a tiny off-grid house in a rural North Carolina community. Powers, who had years of experience working in Latin America and Africa doing conservation and aid work, had recently returned to the U.S. and despite the relative success of his efforts at the local level, was increasingly disillusioned with what he calls a "destructive global system"(xiii). He found himself wrestling with this question: "How could humanity transition to gentler, more responsible ways of living by replacing attachment to things with deeper relationships to people, nature, and self?"

Philosopher that I am, I'm annoyed by this question, since in truth it's not really a question, it's a assertion masquerading as a question. In other words, it's a pseudo-question. As an assertion, it reads: Humanity ought to transition to gentler, more responsible ways of living by replacing attachment to things with deeper relationships to people, nature, and self.

Setting aside my annoyance, I agree with that assertion, and Powers' book is an intriguing description of the transformation that takes place in him, of the deeper relationships with people, nature, and self that he develops, during his stay in the tiny house and its surrounding communities.

I'm bringing up the book now because I've been thinking back to a scene in it where he describes an interaction he has with a father (Paul Sr.) and adult son (Paul Jr.) who have recently transitioned from professions in suburbia to life off grid on thirty five acres of woods, where they were in the process of building several tiny houses for themselves.

After a walk with the pair, Powers reflects on the deeply engrained and widely shared belief in the value of growth and development, at least amongst many residents of the United States:

It is hard to escape our internal colonization, I thought, as I noticed the increasingly anxious looks on the Pauls’ faces. They weren’t unaware of their frost-bitten disaster. [Note: Their garden was hit by frost the previous night.] But more than that there was a vast, raw land around them. They wanted to do things! Build things! Cut trails, dam part of the river for a bigger swimming area, and as Paul Sr. said, 'put a hundred sheep out here.' A slightly horrific vision formed in my mind of their farm five years hence: not this perfectly raw, deer-filled, wild space, but a domesticated pastoral idyll with a summer camp feel. The Pauls would show people around and describe the present moment as those terrible days 'when there was absolutely nothing here.' I recognized this as a symptom of that contagious, middle-class virus that causes addiction, anxiety, depression, and ennui: affluenza. The richer we get, the poorer we feel. To fill the void, we do. I know the feeling. Like the Pauls, I’m American. . . I am conditioned to equate my self-worth with being active, productive, useful.

'Oh my Lord,' Paul Sr. said, a frown settling into his face. “I’ve got a hundred things on my list.'Interesting side note: the same chapter that contains the story about the father and son also describes the author's experiences within a very small Northern New Mexican farming and artist community, which happens to be the community Mike and I now live in. I read this book before we moved here, and when we moved here, I didn't recall ever having heard of this community before.

To return to the passage: it has stuck with me since I read the book and I found myself many times over the past year recognizing in my own thinking and behavior an impulse "to do things, build things," to domesticate, and have "a hundred things on my list." I don't think there's necessarily wrong with this impulse to do things, but sometimes it is compulsive and non-reflective. And sometimes the things we feel compelled to do might be better left undone. I also find it intriguing to think about this urge to do things, to create something new, as a kind of "internal colonization."

I'm often caught up in this urge to do things. I find it hard to sit still or to stay focused on thinking or writing about a particular thing for very long. There's always some other thing that seems to be calling for my attention.

I'm not entirely happy with this compulsive behavior. While it can be positive insofar as it leads to learning and understanding new things, it means that it's difficult to focus on one thing long enough to go into depth and to explore its nuances.

But apart from this compulsion when it comes to ideas, I also experience it as it relates to my physical environment. Wherever I am, I feel a relentless push to create some kind of order: to pick up garbage or dead branches lying on the ground, to plant things, to build stone walls, and to make whatever processes already happening in a place more organized, deliberate, and efficient. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but when I can't create order in my environment or can't do it quickly enough, I am distressed. And once I have created order, I want to move to a new environment so that I can begin the process anew. I don't believe I behave this way out of "affluenza" or because "the richer [I] get, the poorer [I] feel;" I also don't think that it's activity intended "to fill the void," as Powers suggests.

To me, it seems more like a personality trait of mine (admittedly one that my socialization encouraged and one that has been encouraged in many of my peers as well), one connected to my urge to come to know, to develop understanding by organizing ideas in a coherent way. But I see now upon reflection that this trait is not simply about coming to understand the material world; if it was, I'd just look carefully at things, perhaps manipulate them to better understand them, and then put them back as they were. I don't do this; I change things, I am compelled to improve them.

But now I wonder, is it really improvement? Am I really making things better than they were?

Comments

Post a Comment